Review by Anna Stirr

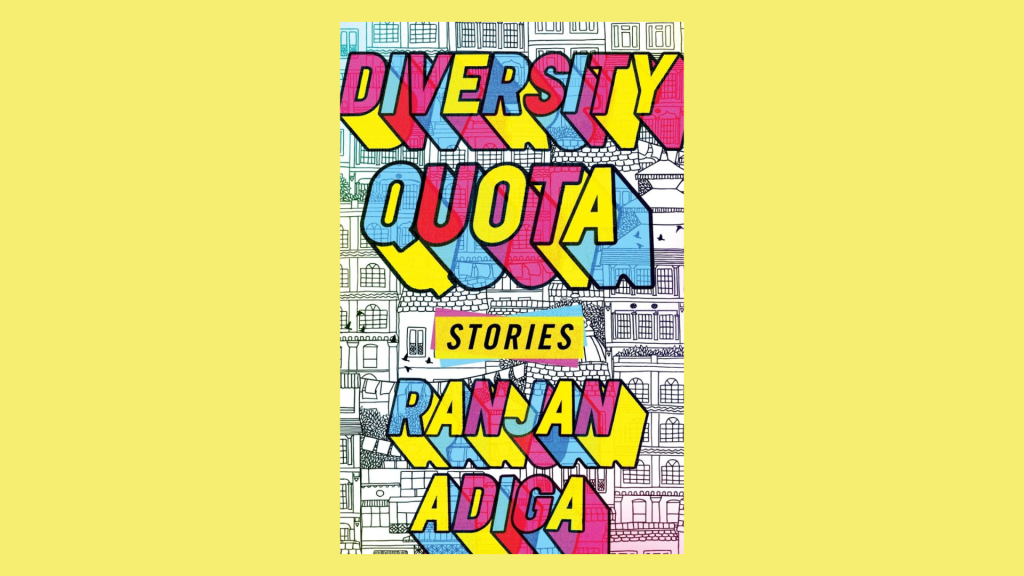

This collection of short stories, Diversity Quota, marks Ranjan Adiga as a fresh voice in global literature in English today. More than simply chronicles of Nepali experiences or of US immigrant experiences with Nepali flavor, these stories demonstrate his skill as a keen observer of humanity.

Set in the US and in Nepal, especially in Kathmandu, with the ongoing connections of back-and-forth movement and communication a fact of daily life (forget having secrets from your family, even when separated by thousands of miles), these stories introduce us to a set of very human characters confronting their own shortcomings. Sometimes it is the immigrant experience that puts them in situations that bring out their worst, but Adiga is careful not to make that into a trope. Whether due to migration within Nepal, to the US, to the US and back to Nepal, or to crossing social or bodily boundaries by adopting a dog or getting a massage, Adiga puts these characters outside of their comfort zones and explores what that space of uncertainty can do to a person. The clash of dreams and desires with the immediate realities they find themselves in shows everyone to be…complicated.

Neither Nepal nor the US is simply an incidental backdrop to these characters’ struggles. Setting here comes to life in the details of social interaction. Everyday social aspects of places shape these stories—the realities of class, caste, race, gender, and religious difference; the politics and hierarchies of these social differences in each country, and their connection (and disconnection) across the miles.

Several stories explore the public spaces of school and work as places where people encounter each other across these forms of social difference, replete with their prejudices, leading to anxiety, faux pas, discomfort, and misunderstanding. A Nepali man realizes his anti-Black racism in his restaurant job somewhere in the US in “Spicy Kitchen.” A Dalit Christian woman faces discrimination and sexual harassment in her bank job, somewhere in Kathmandu, in “High Heels.” A professor oversteps boundaries with his student while trying to fit in with his colleagues at a US university in “Diversity Committee.” A Madhesi student in Kathmandu makes an unfortunate choice that leads to the loss of a chance at a job and a friendship with a wealthy classmate in “Leech.” The private sphere is no stranger to these emotions either; a couple in an arranged marriage negotiate social class in the Nepali immigrant community while getting to know just how different they are from each other in “Denver;” told from the man’s perspective, this first story introduces the theme of male anxiety that appears in most of the others as well, even those with women as protagonists, whose own anxieties are shaped by those of the men around them. Class and gender expectations, roles, and choices come together intergenerationally in the final story, “Dry Blood.”

Readers with one foot in the US and another foot in Nepal may find some dark humor in some of the misunderstandings Adiga’s characters face. One made me laugh out loud: chicken choila misread as butter chicken. A local, Newar, Kathmandu dish, representative of the Nepali protagonist’s home lifeworld, gets flattened into a generic, Americanized, idea of South Asia centered on India. It’s funny because such flattening into generic “Indianness” among non-South Asians or even “Desi-ness” among other South Asians happens to Nepalis in the US all the time. In the chicken choila conversation, the person making this gaffe is the one who the Nepali main character thinks may be his ally, but she turns out not to be such an ally at all. The gaffe could be classified as a microaggression, but the more poignant meaning here is more like this: despite our occupying similar racialized places in the US social hierarchy, the one person who is kind of like me here still doesn’t see me. In this story, “Diversity Committee,” it’s mostly the Nepali protagonist who’s messing up. But whatever we may feel about his mistakes, we still empathize with his desire to be seen. And this is what all Adiga’s characters seem to be looking for: recognition, of their existence as flawed human beings in a confusing world.

Readers may not like these characters. But Adiga’s mastery of dialogue and interiority, plus his eye for the details of social interactions, leads us to empathize with their emotions even amidst their questionable choices, and perhaps to turn our gazes toward our own flaws and biases. No one in these stories is a saint; no one is beyond redemption. And while redemption may not come yet in these stories, Adiga’s attunement to moments of unlikely tenderness, of the cycles of rupture and repair that characterize relationships among flawed humans who care, suggests that it is still possible, for these characters and for ourselves.

Anna Stirr is Associate Professor of Asian Studies at the University of Hawai‘i-Mānoa. She is the author of Singing Across Divides: Music and Intimate Politics in Nepal (Oxford University Press, 2017), and many other articles and documentary films on music, dance, language, intimacy, and politics in Nepal and Nepali diaspora communities in the UK, US, and the Gulf countries. She performs Nepali music as a singer, flutist, and percussionist.

Leave a comment