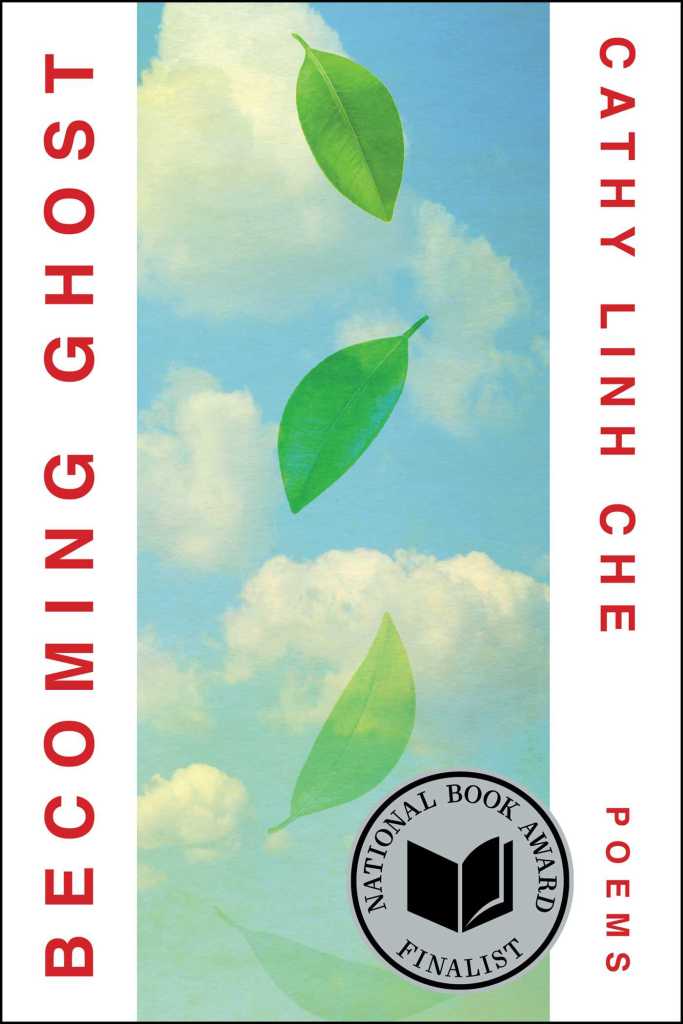

Cathy Linh Che is a writer and multidisciplinary artist. She is the author of Becoming Ghost (Washington Square Press, 2025), a Finalist for the National Book Award, Split (Alice James Books) and co-author of the children’s book An Asian American A to Z: a Children’s Guide to Our History (Haymarket Books). Her video installation Appocalips is an Open Call commission with The Shed NY, and her film We Were the Scenery won the Short Film Jury Award: Nonfiction at the Sundance Film Festival. She teaches as Core Faculty in Poetry at the low residency MFA program in Creative Writing at Antioch University in Los Angeles and works as Executive Director at Kundiman. She lives in New York City.

On October 29, 2025, hidden in the shade of the bustling street of Waiʻalae within Kaimukī, Kona, I had the once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to sit down and have a conversation with Cathy Linh Che. In a quiet corner of Plantoem, a quaint cafe-infused plant nursery, we talked about our own upbringing as Vietnamese diaspora and Cathy’s most recent book, Becoming Ghost, where Cathy documents and recenters her parents’ experiences as refugees who escaped the Vietnam War and were cast as extras in Apocalypse Now (1979). Our haunting conversation was thrilling as we discussed the intimacy of poetry and the Vietnamese diasporic spaces that Cathy upholds as a multidisciplinary artist and poet. During my conversation with Cathy, we also talked about her film We Were the Scenery (2025), which premiered at Hawaiʻi International Film Festival (HIFF), where the film is a contrast to Becoming Ghost, carrying joyful thematics rather than tones of grief and recovery. I am honored to be in conversation with Cathy and to be able to learn how to haunt the world as she does with her craft.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

Timmy Trần (Trần): I want to start with your film, We Were the Scenery. It recently premiered at HIFF, and I was wondering what makes HIFF different from other screenings you’ve attended, and what about HIFF strikes a chord with you?

Cathy Linh Che (Che): One notable thing is, according to what I know of my parents’ story, the first place that they landed after being refugees in the Philippines was Hawaiʻi. Their journey had a layover, in Hawaiʻi, and so the first “U.S. soil” that my parents touched was in Hawaiʻi. And that’s significant to me.

But I also recognize when I say “U.S. soil” that’s very contested, because in some ways, historically, the reason the Philippines offered itself up easily to refugees was because there’s a U.S. naval base in the Philippines. The Philippines was a former territory of the U.S., meaning there’s a strong military partnership that allowed an easy acceptance of Vietnamese refugees who were displaced by the war to be absorbed into refugee life.

Hawaiʻi offers up a similar touch point to my family’s story. I will say that being at HIFF makes me think a lot about indigeneity. I was a part of the HIFF Industry Conference. It’s the first year that HIFF has industry here, and the panel discussion was fascinating, being around how to center your own cultural sphere in production. There was an amazing discussion centering indigenous Hawaiian knowledge, language, battle scenes, writing, AppleTV+’s Chief of War (2025). And that is essentially the project of We Were the Scenery; to take a story that has marginalized Vietnamese people and to have Vietnamese people be at the center and to marginalize the film Apocalypse Now (1979).

We are able to discover humor by shifting the perspective where my parents are the center of the narrative, rather than having them as extras.

Trần: Thank you for sharing. I wish I saw your film at the HIFF screening on Saturday so I could listen to the Q&A session afterwards. I went to the Sunday viewing where it was just the screening, but I was holding back tears. It was special, and it reminded me of my relationship with my mom, especially towards the end of the documentary when she talks about how memory is fleeting and—oh my goodness. It was amazing.

Che: That is moving! Thank you so much for telling me that.

Trần: How did it feel, since you were the writer and producer for We Were the Scenery, to give away some kind of creative control to other people, such as the director Christopher Radcliff and cinematographer Jess X. Snow? How did it feel giving away control of your parents’ story?

Che: It’s interesting because I don’t think I had to give away creative control. I worked with people who were very respectful of the story, and in collaboration, we recognized what each other’s strengths are. I had not directed a film before, but Chris has almost twenty years of directing experience. I’m happy to defer to his filmmaking knowledge.

The same with Jess. Jess has been doing video work and working with cameras for well over ten years as well. And I’m not a cinematographer. It’s not that I need to give up control, because what would I control? Something I don’t know how to do? In this case, collaboration is simply additive. Everybody’s geniuses coming together. Because I have access to a story that is personal, they understand that it is their role to support telling the story in the best way possible.

There have been minor disagreements, but in the end, we know a couple of things: One is that if—and it’s a small team—if two people don’t like something, but one person likes it, then maybe we have to find a third way. We have to really listen and find a solution that works for everybody. So we’ve been able to do that throughout the process.

That’s been really exciting because writers often work on their own, and they do have total control. Even if you’re an editor, especially in poetry, and you make suggestions, they’re always suggestions, you know? In film, at least this film, we shared expertise; therefore, it wasn’t a power struggle; we’re all moving towards a vision.

Trần: Since we are on the topic of film, you had previously talked with Dr. Valerie Nyberg about being a cinematic thinker. Can you tell me what visuals mean to you as a multidisciplinary artist?

Che: Great question. When we’re dealing with a page, they give a lot of room to invoke imagination. When images are on the screen, they’re often opportunities for a different type of immersion into a story. I personally read text with my body, so when there’s a text, I become very attuned with it. Sometimes I’ll also read it with images appearing in my mind as a reader. In film, I don’t have the opportunity to imagine what a character might look like because it’s presented to me. Now, what I have the opportunity to do is still attune my body and my mind to what’s happening on screen, but I’m not creating my own pictures.

There’s a way with my poetry book, if you have a hundred readers, you might have a hundred different movies playing in people’s minds. With film, people might have a hundred different reactions, but they’re not having a different movie playing. This is actually the movie playing.

Each medium offers something different. I will say that text has some limited visual elements to it, so, with the golden shovel poems, I am visually marginalizing Coppola’s words and filling in the space with my parents’ words. I’ll make a distinction: Poetic images to me are a portal into memory and the body, and visual imagery is something people are given and they react against it with their own body of experiences. This is such a great question that I wish I had a better answer to, and I will one day.

Trần: You had brought up the golden shovel in your poetry, and you credited the golden shovel form to Terrence Hayes. I was wondering, How did you come to the idea of using the golden shovel form for the script used: “I love the smell of napalm in the morning.” How did that come to you?

Che: I love Terrance Hayes’s book Lighthead (2010). That’s the book that introduced the golden shovel; that form stayed with me for many years. And then I did a generative writing workshop in Long Beach, California, at The Poetry Lab, where that was the prompt. That was my first experience writing the golden shovel. I experienced a lot of freedom because it looks difficult to write, but it actually—as many constraint-based forms offer—allows for greater freedom within a constraint. The constraint is unique because it’s conversational.

The golden shovel that Terrence Hayes wrote with Gwendolyn Brooks’ lines is homage. It’s an opportunity for Terrence to write from a speaker’s voice. I didn’t know how to write this book, it seemed too big for me to write, how do I even begin? After trying to weigh out what’s the best possible way to start writing, I just decided there is something very simple about using the screenplay in order to marginalize and center my voices. It felt like a simple concept, and let’s just start with that.

When I wrote those pieces, they felt very alive to me. That helped to build and begin the process. Otherwise, I just felt like, “How do I do this—it seems impossible.” Once I began somewhere, I felt the richness in those series. I write in my mother’s voice, my father’s voice, and my grandmother’s voice and I felt that the chorus was powerful. That was what made me feel like I could start with this form, and I could build upon it; I could build upon its possibilities when it comes to my family’s story.

Trần: Talking about building upon your family’s story, by using their voices, how could you use the golden shovel as a way to evoke memories?

Che: I mean, much of my process with writing these poems involved interviewing my family and transcribing interviews. The act of recording the memories that were told to me, verbally, is, in my mind, evocative, right? So, it’s like an oral history. That’s a root of poetry, and it’s a root of memory keeping.

Trần: I recently learned from one of my classes how the golden shovels can be used as a form to regain agency and to control the narrative. What was your experience and process like trying to regain that agency for your parents with the golden shovel?

Che: It felt like I was able to bring the fullness of my entire family with me. It didn’t feel like I, myself, was only gaining agency. That gave me a chance for me to speak, but also it was an opportunity for my family to speak, and be heard, and anybody who’s been marginalized to speak and be heard.

I have a poem in the collection in the voice of Steven Yeun, who was Glenn Rhee in The Walking Dead (2010–2022). I wanted to write in that voice because I was compelled by it, but also because it’s layered with my father’s story, my mother’s story, and my story where, we are presented with this beloved character who finally is an Asian American representation on camera, who’s complex, and has his own journey. But then, of course, we had to sacrifice him. And so, his self, as an actor, lives on after his character was killed off. In a way, I’m trying to, as a writer, think about what happens when the script diminishes you. How do you actually use writing to think beyond the script that somebody else writes for who you are and how narrow a role you get to play? That’s part of it. It’s about extending the story.

Trần: That’s amazing. What you do after the script… I’ve never really thought about that.

Che: I didn’t think about that until now. It makes sense, what I was subconsciously thinking about.

Trần: I really wanted to talk about your parents and share their story as well. They’ve been a big influence for Becoming Ghost and We Were the Scenery—what was it like to share your parents’ story with a public audience? Did you feel vulnerable at times? What did you feel making that decision to put them into the limelight?

Che: I have a lot of questions about the responsibility that one has, and the ethical considerations one might have. That’s more obvious in the book than in the film. But, my critique of Coppola is that he’s taking people’s bodies to authenticate the film. My question is, as the person in my family who has adopted the English language the most powerfully—and it’s such a colonial language, it’s this world language—what is the aim? The first time I showed my parents a version of the film, they watched the three-channel video installation version, which is twenty-eight minutes long. They didn’t seem to have a reaction afterward. They didn’t talk about it. It doesn’t mean they didn’t have a reaction, but they didn’t chat about it afterward, and as you know from the film, they are chatty.

That made me wonder if, actually, the film is not for people like my parents. If it’s for me, for Vietnamese diasporic people, or this generation that is steeped in English, or people who know Apocalypse Now. In some ways, the story, even as it honors them and loves them… It’s not fully for them, even if I think it’s for them, they might not need it. My parents’ lives are very full, they feel like they are the center of their lives. I don’t feel like their story is centered within the greater canon of American films and American literature. That is the space I’m trying to have their voices belong to, but they don’t care to belong to that space. Because they, like I mentioned at the beginning, belong to a Vietnamese community that shares their story, it’s not as urgent. But for me, as I am moving through the world and not seeing their voices on the bookshelves, I know that their story adds a lot to the story of the war or of film history.

Trần: You’ve previously talked about how your film is a way to express joy, and then your book Becoming Ghost carries more of a darker theme. How do you work in both mediums to curate a balance to tell the story?

Che: Yeah, I wish my poems were more joyful. In fact, that’s something I’m thinking a lot about. It’s more natural for me. My poetry tends towards grief and critique more readily. And the film, because my parents are speaking and driving the whole thing, they tend toward real talk and humor. I think of it as being conversation, because there’s a lot I can learn from my parents, how to talk, and how they express their story because they are very poetic.

There’s nothing untrue about the ways I’ve represented my family’s story and Becoming Ghost, because they were derived from our interviews. But the truth is, life is not made up of just the most high points of loss. I see that with my parent’s lives, and that affects how the poems come out. For my parents, when they tell their story, which is filled with the images of us growing up as kids, building a family, a real life that can’t help but be very fun.

I think of it as a conversation and a growing one, an ongoing one, that I hope to continue to build on.

Trần: Definitely. I remember a scene in the film where one of your parents pointed out, this one lady, she was three months pregnant and she fell! And then your parents brushed that off. But in Becoming Ghost, you focus on how horrific that is, that she kept falling and falling again while being pregnant. I definitely see the conversation that you’re having with both.

Che: Yeah, I mean, in one of the interviews, my mom does say, “Oh, isn’t that gruesome?” That’s in my prose that I’m writing. I think that a story has many different points of view and sides and voices, and I think of my work across genres, helping to capture multiple nuances and vantage points.

I’ll give you another story real quick. I have always heard one story from my mother about her leaving at seventeen, to go from Đà Nẵng into Sài Gòn. And she was like, “I was going to look for work,” and then I met my auntie, who was only four years old at the time. She told us an entirely different wedge of the story that I never heard before, which was that my mom buys her this ice cream cone, and she’s like, “Take care of our mother for us.” My auntie’s read on it was, “Oh, your mother left because your grandmother nagged too much.” But when I brought that story back to my mom, she’s like, “No way. Like, no, I needed to find work. I needed to find a way to take care of myself.”

This back and forth of these layers of story where, if you just keep adding voices into the conversation, you’ll get a fuller story—what’s true or what’s not true is unknown—but it’s richer for it. And genre, for me, offers that. It offers the possibility of richness. Going back to your image question, something about the film that I love is that it doesn’t leave what my family looks like to an imagination. It actually presents what we look like and how we look. There is this force of insistence of what we are visually. Another thing that film offers is sound. You can hear the score of my family’s laughter and seriousness and secretiveness, and voices being in there. The poetry always has a score that you can hear, it’s rhythm, it’s meter. But it’s just different out loud.

Trần: Thank you for sharing that. Yeah. Oh, my gosh. Now I have a different perspective of how that visualizes poetry. I never really considered sound as a medium.

I want to move into your craft. What is part of your crafting writing process for poetry and even for film? And, for example, are they different in a way or are they the same?

Che: Poetry comes very intuitively to me. A lot of my craft training came early on. I had a creative writing teacher in high school who taught me the elements of poetry: when I line break, where I write with specificity rather than generalities. These are ingested as things I learned as a fifteen year old. Part of craft is the absorption of it. The study of it, the absorption of it, and therefore when it comes to the page, it is now the combination of that study, that comes with reading, that comes with just thinking about, what is poetry, and breath, and all of these things. What is imagery? It just emerges.

There’s also this other thing about craft, which is like an invention. Poetry, historically, comes from an oral tradition. How do you craft it? You craft it toward things like memorization. That’s why much of poetry early on rhymes and has rhythm almost like a song. You could sing it or you could memorize it. That’s why it’s an element of poetry that people in academia have extracted into this study. The other aspect of craft that I always think about these days is the proliferation of the MFA program in the United States, which can be arguably traced from the Iowa Workshop, that was shaped and funded by the CIA during the Cold War in order to create a literature that served the state, that was more in line with individualism and capitalism over communism and communitarian ideals that could potentially overthrow capitalism. I was talking to somebody who was part of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop in the ’60s, and he was told directly, “You don’t write about politics in your poetry. You don’t write about the war.” He was a Vietnam War defector. We’re inheriting that legacy now where oftentimes craft is used to make you think that the most important thing is the line break and not poetry’s power to illuminate a new way of understanding power, or the power inherent to poetry. There’s a lot of people who think and say things like, “Oh, you’re studying poetry. That’s so indulgent,” because people have marginalized poetry or the art form. Even as they are trying to control media and language and narratives in this way, there’s this obvious power that language has, and then there’s this sense that poetry does nothing. And part of that is because it’s been defunded, and treated culturally as in a capitalist society as having no value, no worth, and no power.

Recently, Fargo Nissim Tbakhi has inspired my craft. He has an essay called “Notes on Craft: Writing in the Hour of Genocide,” and it asks, What does it mean to write as a Palestinian writer during a time of genocide, and what does it mean for all of us writers who are writing from the imperial core. Tbakhi’s contention is that if we can move craft away from this idea that it’s just broken down into line breaks—he calls that sanitizing influence on American literature—and move it toward political education, that would be revolutionary—in fact, and a prerequisite in some ways into writing that feels accurate, responsible, truthful.

I think of short films as the poetry of the world. They make no money, and because they make no money, they can be really weird. You can be experimental and actually say things, and they’re not there for a market reason. These short films are oftentimes to deliver a message, or to convey an aesthetic point of view. In that sense, I feel like I felt a lot of freedom in making a short film.

Trần: I wanted to touch back on what you said about the power of language. In both the film and your book, Vietnamese was used and prevalent in the film. Do you often feel that language gets lost in translation sometimes, especially working with Vietnamese?

Che: I translated the entirety of the film from Vietnamese into English. The subtitles are not perfectly accurate, but I had to translate for context too. I tried to get the spirit of the writing or the speaking across. I don’t actually think that too much is lost in translation because what you receive is a pretty good translation of what my parents say. You get the laughter, the back and forth laughing, as a central, essential component of their communication. I’m fluent in both languages, but not as good as I would like to be in Vietnamese. I do think that while something is lost in translation, it’s also gained in the dual languages existing, because if the right word is better in Vietnamese, I use Vietnamese, but then at times, some words might work better in English. Even my parents, when they’re speaking Vietnamese, it’s like Viet-English, where English words are sprinkled in. In the same way, my parents are using the word that is the most communicative.

Trần: That’s beautiful. On the same topic of craft and writing. What are some inspirations that you draw from, what do you absorb from? And who are some of the people that inspire you?

Che: There are many people out there who inspire my work that I love. I feel well read and deeply underread all the time. I wish I could turn off my Instagram addiction. For every time I’m touching Instagram, I wish I could be reading a book instead. I wish that was my life––watching a movie or nourishing my brain rather than just pummeling it with advertisements.

Anne Carson is a huge influence on my work. I studied with her at NYU. She led this amazing class called “Egocircus,” and it was a collaboration course that encouraged all of us to collaborate with others and think about what our strengths are.

I did a translation project with all these people speaking different languages. I had a project that was from a series of women and femmes who had experienced sexual violation. There was also one project where I had gathered all the Catholics together to work for my project. There was somebody who was a dancer, and it was a poetry and dance collaboration. There was somebody who knew how to do fabric work and at the time, they had not conceived of bringing in these disciplines together. Poetry and daily life were two concepts that many did not think could coexist together. That combination was the first spark of thinking that these sorts of things were possible for many of us. So my friend, Bianca Stone, in that class, started doing poetry comics. It was just the seed of this idea that poetry is expansive. It’s not solitary. It’s communal, and it’s collaborative. That was amazing. Anne Carson’s huge for me.

Sharon Olds is huge for me, because she started writing poems that were very personal, and just really got up in the body with sex and visceral imagery. Lucille Clifton’s work is condensed and complex, and she also wrote about sexual violations. She was somebody who really paved the way for me to not be alone.

Those are three good people to start with, but I have many more who I love.

Trần: Let’s talk about inspiration from beyond the living, ancestral work. I believe ancestral work is important to Vietnamese culture and practices, and you talked about using séance as a way to invoke your grandmother’s voice. How did your ancestors help you in the process of writing Becoming Ghost with using séance?

Che: My first book was a process of managing grief. The losses that come from death, war, and also, a loss of agency, and sexual violation. All of these things felt like such an immense loss. Becoming Ghost is the beginning of this recovery project of gaining access to the voices of people who ostensibly are no longer with us. I think that poetry is a way of bringing people back to life, even though I don’t consider them to be dead. It’s a way to merge time, the presence of a poem means that the past is present, and that the future is rewritten. The future no longer has to be one of absence, erasure, loss. Poetry is this intervention.

Trần: I love your perspective on perceiving time, it’s so much like a spiral rather than a linear.

Che: Yes. That’s why I have a hard time with the demands of prose being all about linear time.

Trần: I agree, because we’re always constantly living in our past and our future.

Che: One hundred percent!

Trần: And decolonizing time in itself is an act of haunting.

Che: Yes, that’s true. Absolutely.

Trần: I would really love to talk more about the process of creating conversations between the living and the dead through poetry. Can you talk more about that?

Che: I wanted to say something about what you mentioned about decolonizing time. It’s interesting because, and I don’t really understand it fully, I was chatting with a friend who is a poet, who is part of Indigenous Nations Poets. She was talking about decolonizing. There’s a real move toward futurisms and indigenizing English. Instead of decolonizing English, it’s indigenizing English. To imagine not just going back and correcting the brutal past, but to think about the future. I think oftentimes, people think of indigenous people as people in the past because they have been subject to violence and loss. But to imagine indigenizing, it’s like a productive future, a regenerative process. English is a living language. It’s something that we have influence and power over as practitioners.

You have words like “phở.” That’s not an English word, but now it’s part of the English vocabulary. Then, you can trace the etymology, “pho (feu)” in French is for fire. These words are changed around, but there are all of these possibilities for language and invention and reclamation that can exist within that.

Okay, I went sideways.

I come from a religious background, but that’s really layered, too, because… Catholicism’s a lot of chanting, but so is ancestral work. When I go to my grandmother’s grave, there is a sense of ritual. You have the smoke, and the smoke is its own language; bowing is its own language; there’s talking; there’s chanting; there’s all types of ways that you’re speaking to the dead. You’re offering food, and that’s conversation. And so, I think of poetry as all of these rituals and possibilities and mediums kind of put together as a bridge between the two. As a shared language, the realm of the living is sort of a space and plane that sometimes people within capitalism are really cut off from the other realm of who’s “dead.” There’s something very cold and Western about imagining that you have no relation to the past, that you have no relation to people who’ve come before you; that allows for a person to look at people and land as a resource to extract from. There’s a way that we integrate the language between the realms of the living and the dead, that reintegration tells you that you’re not alone.

There’s more to life than the cold extraction that happens when you feel like, “Oh, I need to pay rent and buy food, and all of these things, and I’m very separate from other people.” We’re communal. Living and dead means re-communing with other people generally.

Trần: Your answer reminds me of “A Glossary of Haunting,” which is an essay by Eve Tuck and C. Reed, and the way they talk about how haunting is the audacity to remember/stay. In the same regards, what does haunting mean to you?

Che: That’s a good question. “The audacity to stay” is such an interesting thing because it assumes that the dead should be located in one area and the living should be located in one area. The more we can open up that porousness, the more connected we feel. I think of haunting as actually the rupture between people of realms. How do we open those doors to create and exchange? Then it no longer becomes haunting. Because what creates that haunting is this sense of separation. What releases that haunting is opening up a feeling that there is integration rather than separation.

Trần: We are almost at the end of our interview. I just wanted to say congratulations on being a finalist for the National Book Awards. So exciting! That being said, what does it mean for you now to be a Vietnamese, Champa, American poet and multidisciplinary artist?

Che: I’m very excited to share that space with my family and other people who have been relegated to the margins or the background. I want to continue to take seriously the role of bearing the responsibility as a poet and multidisciplinary artist and to create new pathways for not just myself, but other people. What I mean by that is every day I’m thinking about the power of what we do and in seeing how poetry, filmmaking, making art, making community, is actually a way to change our worlds and balance of power.

Trần: I really wanted to ask you this question. You previously talked about how you can weave through these three identities, Vietnamese, Champa, and American. Can you explain that intersectionality that you have?

Che: I want to actually talk about the Champa side, because it’s something that’s relevant to my last name. I was named after a singer, Che Linh, who is Cham. But, it’s an unknown culture to me. I’ve only been to a museum in Vietnam, I’ve only read a couple of Wikipedia articles, and I’ve met one person who is, like, part of the delegation of UN of Cham people and because of this, that is why I’m very interested in understanding indigeneity and power. The term “Vietnamese” also means to me the conquering of this indigenous kingdom. In the context of the U.S., Vietnamese people are seen as victims. But the military always studies the Vietnam War, because it’s the war that the U.S. lost. How did this group of people beat us?

Part of this identity is about power. It’s about responsibility. It’s also about solidarity. That is something I didn’t mention that I feel very strongly about. Much of my solidarity arises from the knowledge that my family has experienced great loss, which is very embodied to me, even though I’m the second generation and experiencing it secondhand. I want to record and tally up those myriad losses, but also recognize it within the system of fullness. Because the truth is, yeah, the kingdom in Champa was conquered, but I’m still here. Yeah, the South Vietnamese lost the war, and I’m still here. I was probably born of that war. How do I not see it just as positive or negative but estimation of all of the potential. English is this violent language, but it’s also a potential site of regeneration too. I think that’s the main thing. I’m on this new journey of “it’s not just about loss,” but it’s about “how we can regenerate.” Thinking about Apocalypse Now, I didn’t even consider that it’s about the end of the world. But, the world’s still here and we have much that we can do to make it more beautiful.

Trần: I love how you talk about how we are still here, even at the end of times, we are present and alive. Moving onto my last question, in Hawaiʻi, our relationship with the land is very important. It’s the core value of our life. And I’m really interested in how you would describe your relationship with your land and as well as your homeland being a diaspora.

Che: In Hawaiʻi, the land is still growing. Despite the terrible theft of Hawaiʻi as a result of the U.S. government’s aims. But the land is still going and people still tend to it. In Vietnamese “nation” means water. So there’s also this sense that the homeland is expansive. It’s the totality of all these spaces. The body is a homeland, and all of these lands that one touches. They all can be places that you love and that love you back. There’s possibility instead of only loss. You can’t ignore loss, but it’s not true that it’s only loss.

Trần: Thank you so much for having this interview.

I love talking to you, and I remember you talking about why you wanted to become a poet, and it was because of how little representation was lacking in the world. Now you’re here and you’re my inspiration. Oh, that’s beautiful. It just really means a lot to talk to like another Vietnamese poet.

Che: Yes! We are here!

Timmy MH Trần is a Local Vietnamese writer and filmmaker. Born and raised in Honolulu, Trần grew up on Oʻahu, Hawaiʻi, playing in the red dirt of Kaimukī. Trần is the author of the poetry collection, Nước Mía (2023), winner of the Young Writers of Hawaiʻi Award, and writer of the screenplay, Deep End (2024), winner of the School of Cinematic Arts Abernethy Screenwriting Competition. Trần was educated at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, where he graduated with a Bachelors of Arts in Digital Cinema and English.

Leave a comment