Review by Alexa Cho

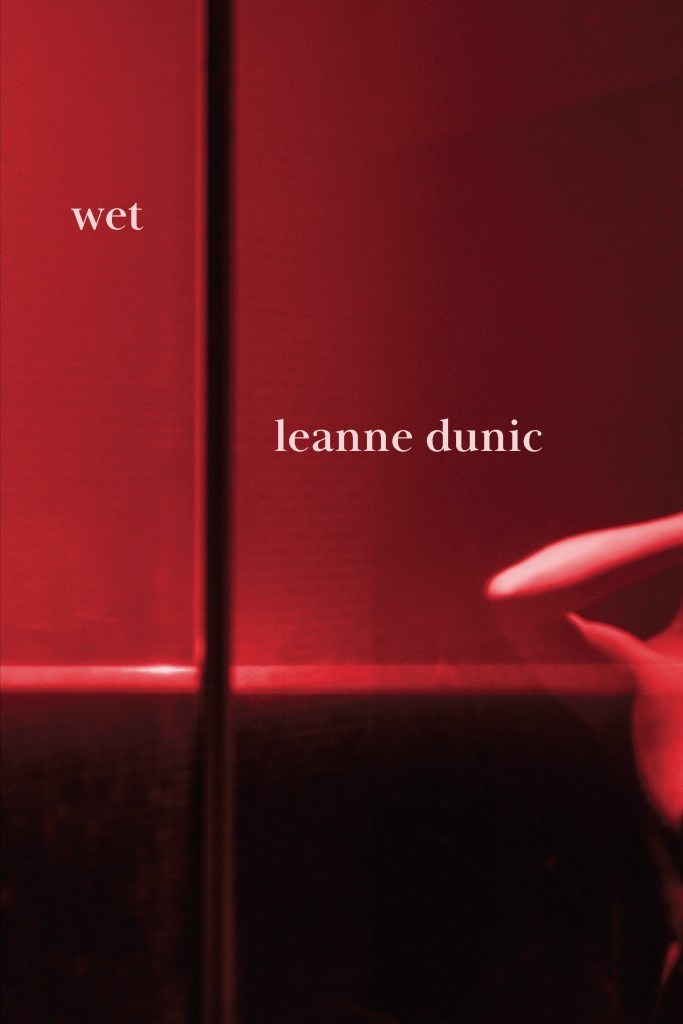

Whether in geography textbooks or a Google search, Singapore is often exalted as a country set apart by its technological advancements and high standard of living. However, such a notion is only one perspective of Singapore and not necessarily the most accurate. Author Leanne Dunic draws on experiences from her artist residency and as a former model and boutique owner in Singapore to create the world of Wet, a hybrid book of poems, vignettes, and pictures. Set during the 2015 Southeast Asian haze, a period of heavy air pollution due to rampant forest fires in a dry season, Wet depicts Singapore under the sardonic and sexually charged lens of a Chinese-American model navigating what it means to live in a time where even the air is toxic. Her fellow models smile for photos in a way that hides their desperation to make a living while starving pigeons feed on poisoned bread prepped to thin their numbers, making a compelling argument that a paradise is just a land where suffering is sufficiently hidden. As the reality of migrant workers and the questionable divide between humans and nature are brought to the forefront, even those familiar with Singapore can find a new viewpoint in which to view this country of smoke and mirrors.

Leanne Dunic renders Singapore in a complex way by filling her narration with the array of animals, people, and perspectives that dwell within. Much of the book is the narrator pondering the endless string of questions and moral quandaries that come up in her routine. Should she feed the pigeon only for it to die later? What is necessary to survive and what is indulgence? None of these questions have simple answers. The narrator’s tenuous existence exemplifies the book’s fluidity and the tension within Singapore: she wrestles with Mandarin, a language she’s not comfortable with, to make the barest connections; she craves intimacy while needing to protect herself from her client’s sexual advances; and she wars with herself on whether to remain in Singapore or to retreat into a future unknown. The residents of Singapore from the pigeons to the construction workers are also as reflective of the story’s themes as the narrator’s own proclivities. Namely, they highlight the exploitation needed to build paradise.

Singapore, Hawaiʻi, and so many other “tourist destinations” have long histories of luxuries coming at the cost of natives being “priced out of paradise,” making the themes of Wet both achingly common and important for readers. Wet does not hold back in explaining all the ways gentrification and labor exploitation hurt Singapore’s citizens. Numerous short vignettes and poems are simply the narrator living her life, but she constantly witnesses heart-wrenching moments in the process. Take the section on Little India where she notes both the men making prata dough and a man’s cry as he is dragged off by the police. But most of all, I appreciated how Dunic depicted these grave and complex social issues in a way both enjoyable and poignant to readers. Her narration fluidly shifts between painfully honest truths and being hilariously relatable. Moments such as the narrator “sending silent prayers to the deities of Pepto Bismol” during a bout of food poisoning and affectionately calling a girl “Strawberry Cheesecake” for her endless appetite for the ice cream flavor add a refreshing contrast to the bleak subject matter. Through this balance, I felt as if Dunic was peeling back the layers of Singapore and breaking them into pieces for me to digest rather than forcing me into the narrator’s viewpoint. Many choice details like the maid who “ran away” from their work rather than quitting are undoubtedly unsavory, but the wry and succinct prose avoids inflating these events into melodrama.

The forms in which Wet’s messages are delivered are also as diverse as its subject matter. Wet is replete with dynamic and original forms of storytelling, breaking barriers between genres and incorporating images to visualize what cannot be described. One of the most unique aspects of Wet is the way Dunic uses photographs throughout the narrative. The photos of beaming mannequins look hollow compared to the distant, diverse commuters, and the city-dwelling pigeons appear frantic compared to a lone turtle drifting in a pond. Moreover, as Dunic writes about the burdensome construction the narrator passes, she presents pictures of ugly tarps and half-fixed roads that run contrary to Singapore’s pristine image. Prose-wise, each page also kept me guessing as to how the narrator’s thoughts or experiences would be presented. One page might provide a peek into the narrator’s character through a fortune-telling session while another is a feral reimagining of Snow White that embodies the book’s ecocentric themes.

With all of Wet’s moving parts, it does initially feel difficult to see where the metaphors end and the city begins. However, all beings desire water. Dunic grounds her narrative in the desire for wetness that pervades all of Earth’s creatures. These seemingly disparate themes of climate disaster and migrant isolation are mirrored in how the search for wetness can be both animals scrounging for drinking water during a drought or the narrator lusting for the wet intimacy of sex. Water and its bonds between beings are extrapolated to our human need for relationships. As the narrator searches for “wet” relationships in the hostile, lonely city, readers can see the way the language barrier separating the “multilingual” citizens hampers her (and migrants like her). Pigeons also drink dirtied water left by construction workers cleaning their hands, tainted by their desire to survive and Singapore’s need to “improve.” Both humans and animals desire to survive and those desires are all too often exploited to make money.

Leanne Dunic binds her readers in the suffocatingly dry Singapore setting while also letting them loose in a world of fluid forms and diverse subject matter. I myself relished the way the narrator’s sardonic voice is used to describe the diverse cast of characters around her. Although Wet’s premise may seem simple at the outset, Dunic provides more than enough hooks to latch onto. Just as the narrator and her pigeon neighbors find themselves trapped in spite of their ability to fly free, so too does the reader find themselves enraptured in the freedom of Wet.

Alexa Cho is a Native Hawaiian senior undergraduate who is currently studying English and Japanese. She enjoys writing prose fiction in a mixture of genres and on an assortment of themes, taking particular interest in the imaginative power of speculative fiction and dark fairy tales. Through her time with Mānoa Journal, she hopes to interact with stories from all corners of the Pacific.

Leave a comment