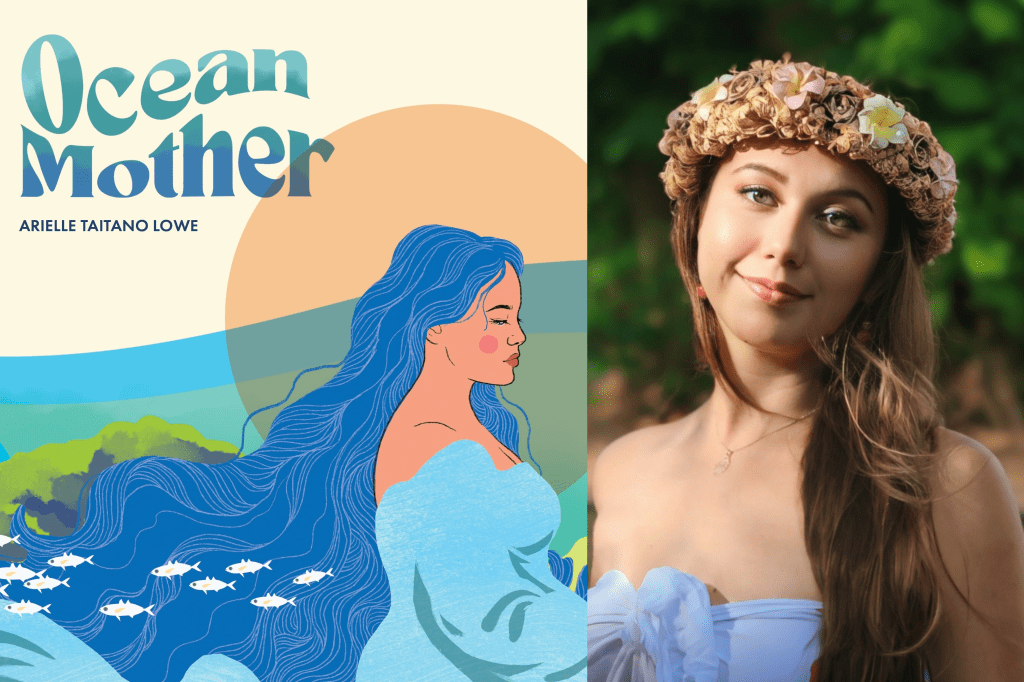

Arielle Taitano Lowe is a CHamoru author born and raised on the island of Guam. Her collection Ocean Mother debuted in March of 2024. She was a 2021-2022 Indigenous Nations Poets Poetry Coalition Fellow and is currently working towards her PhD in English at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa.

On December 10, 2023, I attended the Washington Place Poetry Workshop hosted by Hawaiʻi State Poet Laureate Brandy Nālani McDougall. This workshop was the first time I had met Arielle Taitano Lowe, but it was not the first I had heard of her. As you will see in our conversation below Arielle and I have had possibly many instances in which we could have met before. My sister and her first cousin married over a decade ago and because the family was so welcoming to us we spent at least 10 years of birthday and holiday celebrations together, yet Arielle and I had never formally met. You would think on an island as small as ours that everyone must know everyone, but Arielle and I have debunked that stereotype. It took moving 6370 kilometers and a couple years after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic for our paths to cross and truly become woven like they have today. It took Ocean Mother being written for us to have our first one-on-one conversation which strengthened my belief that our ocean helps us find our way to one another no matter the distance and as Arielle says in this interview to “be that ocean for one another.” Following that workshop, I kept in touch with Arielle through social media and awaited her debut. It was a communal diasporic celebration. We sobbed during “Soul Fishing,” laughed during “Chamaole,” and were left warm by the gift we were given. It has been an honor to interview Arielle and to help readers dive deeper into Ocean Mother.

Lauren Taijeron (Taijeron):What does it mean to be a palao’an (CHamoru woman) born and raised in Guåhan with a full length poetry collection?

Arielle Taitano Lowe (Taitano Lowe): The first thing that comes to my mind is responsibility. There’s a lot of responsibility to acknowledge the work of the CHamoru women before me that allowed this space to be possible. In my life, there’s the women in my family, my grandmother, my own mother, [and] my aunts who instilled a love of language and reading in me. Historically, we have CHamoru women activists who have opened up these spaces. I think of Kisha Borja-Quichocho-Calvo, who was my creative writing teacher in 11th grade. She taught spoken word, slam poetry, and introduced us to authors from the Pacific, including Hawaiian, CHamoru, and Samoan authors. It was the first time I had read or listened to Pacific Island poetry. And I was like, Dang, I dig this. I’m also thinking of Anne Perez Hattori and C.T. Perez. I think of [the word] “collective.” I’m trying to find that balance between being confident and proud of my work being the first full collection, and then also acknowledging the many hands [that] have been involved to make this book happen.

Taijeron: That gratitude for the collective is really apparent, not just in your answer right now, but also within your book. You’re so incredibly giving in it. How did you make these decisions to be so giving in the book, to provide that history, to provide that gratitude for the collective, and to provide translations? Other authors don’t always do such a thing.

Taitano Lowe: Wow. Well, first of all, I love it’s you asking me that question because we’re related through you being sisters with Alex, who’s married to my cousin Nicholas Garcia. My other cousins Kianah Garcia and Devend Cruz actually played a large role. In 2014, when I first started learning CHamoru, I would post journals on Facebook, prompted by my CHamoru professor, Dr. Michael Lujan Bevacqua, [who] had this challenge to flood social media with as much CHamoru language as possible. As a learner, at the time, I didn’t want to put the English translation in the social media posts because I wanted it to be a CHamoru language only space. There’s an argument that if you don’t put a translation, it forces your reader to put in that work, to find the dictionary or ask someone, then it becomes a connection they can make to learn the language. My cousin Kianah, she had mentioned at a family get-together, Oh, that’s so cool that Arielle’s learning Chamoru, and my cousin Devend, in a warm and kind way, had asked me in the back of Grandma and Papa’s house, Hey, cousin, that’s so awesome that you’re learning CHamoru! Can you leave the translation so we can learn too? The reason why I always provide translations now is because I think of that moment. There is a need. There is a hunger. And I’ve had the community ask me, Can you please make this accessible? I love being able to and I will continue to do so for the unforeseeable future.

Taijeron: Providing translations was absolutely helpful. What was just as helpful was the foreword and preface. I had to wait until undergrad to learn about CHamoru literature and other cultural practices. But now when kids receive your book, they can have this history. So many people are going to be grateful for it. Thank you for that. My next question is about all the different forms you’re playing with. What are the various poetic forms doing for Ocean Mother?

Taitano Lowe: When I think of the various forms in this collection—spoken word, free verse, ecopoetry, the golden shovel, and documentary poetry—I was hoping these forms would tell a story in a multifaceted way. The first word that comes to my mind is the Native Hawaiian concept of mana or, in our language, kåna. Certain stories, certain people, have so much mana or kåna that one genre is not enough to convey or express that story. One example from my book is the character Johnny Atulai, my papa, who I talk about in “Talayeru,” a free verse ecopoem, [and] “Johnny Atulai,” a documentary poem. They gave me a different access point to tell this story.

In my most tender moments, it makes sense for me to write or to compose in CHamoru language first which is how “Trongkon Nunu” and “Ocean Mapping | Apapa” were initially composed. I’ve been able to be my most authentically emotional self in our language. That comes from listening to how my grandma has told stories. It hits different when she starts talking in CHamoru about her experiences. It’s like, when my grandma was teaching me how to make the dough for buñelos aga (banana doughnuts)—you just know when it feels right!

Taijeron: I’m wondering what opportunities you’ve had to share with youth and how has that been received? Additionally, have you had any experiences with elders and how they responded to your work?

Taitano Lowe: For youth, I ran a series of workshops last year and it seems to me they really love the poem “Chamaole.” It’s the poem they tend to connect to the most because it’s about mixed-race identity. During the editing process, a couple of very well-meaning mentors asked, Do we want this poem [“Chamole”] to be in the collection? It’s very clear that the author was much younger when this poem was written. If you take a poem like “Chamaole” and compare it to “Trongkon Nunu” or “Ocean Mapping | Apapa,” it’s so different.

With elders, the poem that seems to connect the most is “Soul Fishing.” My grandma had read [it] at the Purple Heart Christmas party a couple years ago. In her words, There wasn’t a dry eye in the room. My grandparents have championed that role of sharing my work [with elders]. I’ve been reflecting on how I can engage with our elders in a more artistic process. I’ve mostly been in roles where I’m listening to and honoring their stories.

Taijeron: I love how your grandparents are sharing those poems. Next, I wanted to ask about authenticity and belonging. In Guåhan, the colonial history and present systems can lead us to believe we are not authentically CHamoru. You explore this in your article “Rhetorical Dance of Belonging: Chamaole Narratives of Race, Indigeneity, and Identity from Guam” as well as throughout this entire collection: “Chamaole,” “Chamoru Kaikamahine,” “Dance.” Our community has been revitalizing language, dance, and realignment with our ocean region for decades. I feel that authenticity, rather than being something that assists in realignment/revitalization, has instead hindered us and our Pasifika siblings. So, I return back to your ideas on belonging and ask, Why does knowing who and what we belong to matter to you?

Taitano Lowe: Beautiful question. A story that comes to mind for me was deciding on my master’s program. I had applied to the UH Mānoa creative writing program and to the Masters in English program in Guam at UOG. Long story short, I was accepted to three other [Mānoa] programs that were not creative writing, but housed within English. I remember being at Angel Santos Memorial Park and I had already accepted the offer at UH. It felt like this heavy weight, pushing down on me. I wanted to just fall and stay cemented to the ground forever. At that moment, I had started crying. I knew I couldn’t leave yet.

It allowed me to do my master’s at UOG, and in that program was the start of the essay, “Rhetorical Dance of Belonging.” My ancestors knew, We’ll send you off eventually, but you have more learning to do at home. I had so much more confidence. Because I spent that time cultivating my own cultural foundation, I had more to share. For the most part, [I have been] unshaken in my identity in Hawaiʻi.

I appreciate you asking, What is this balance of knowing who we are/sharing it with others? Being non-Indigenous to Hawaiʻi, what does that mean in terms of my responsibilities? This is such a CHamoru answer, but it really comes back to respect. And if we don’t continue to teach our children these values of caring for the land and for each other, then that critical foundation will be lost. That will prevent us from connecting with other cultures.

Something I learned from spending time with other Pacific relatives who have a scholarly, cultural, and emotional intellect is you need all three to be a scholar of the people. If you’re going to be an academic and part of our community, there is a responsibility to the cultural and emotional. Whether you’re at home or away from home, whether it’s in your family or your friend groups, you have to surround yourself with people who are envisioning a better future for all of our communities. We can’t have a politics of subtraction. We can’t have sentiments like you’re less than or you’re not enough if we want our culture and values to survive.

Taijeron: You open us with “Ocean Mapping | Apapa” which poses the question, “Who will teach us the ways of the ocean / if not our mothers?” Initially, I interpreted this as a call to the matrilineal society, but later I realized the question might not have been so rhetorical. I felt poems such as “Daughter of Divorce,” “Disatenta,” “Soul Fishing,” “Introspection,” and “Birthing Bloodlines” explored familial trials demonstrating a less “traditional” experience learning about the ocean, where your mother is seen as being absent and leaves you to learn about the ocean from other caretakers. Was this a call to the ocean having a fluid sense of care? What does it mean to diversify care? How do these poems help us in understanding elders as fluid and complex?

Taitano Lowe: Oh, this is so brilliantly worded. Happy tears. I love that phrase, “fluid sense of care.” It’s definitely layered with meaning. So, “who will teach us the ways of the ocean / if not our mothers?” is definitely pointing rhetorically to our matrilineal society. It’s also hidden with lamentation. The damage of my relationship with my mother is very colonial in origin and I have leaned into the ocean as being my mother.

Care is fluid and I think it’s always been that way for Chamorus. Why is my papa more present than my father in this poetry collection? I don’t see it as a bad thing. It’s so common for grandparents to step in and be part of this village of care. I wrote the bloodlines series in this book when I came to Oʻahu, August of 2020. At the height of COVID-19, I was utterly alone for the first time in my life. That was also when I decided to go no contact with my mother. There’s not enough representation and advocacy for children who decide to go no contact. It’s against our biological, spiritual, cultural training, right? And that severance felt very similar to that mahålang feeling (a feeling of longing so strong you feel sick or unwell) of being away from Guam. It was a time of deep reflection for me and figuring out what are my boundaries in the wake of colonial violence that we inherit as Indigenous people. For those of us who are faced with the need to go no contact with certain family members, how do we replace that care? Because when you cut off a relationship, you’re cutting off access to so much love too. People are multifaceted. I don’t want to be the kind of author that entirely paints my birth mother as a villain. I actually have a very nuanced and compassionate understanding for her inheritance as a Chamorro woman born in the 60s in Guam. Those were tough, tough times, the height of American assimilation, especially for a daughter of a Vietnam veteran. We still need intimacy. I still need my mom. I wish I could have a relationship, but it’s too dangerous for some of us, and so the ocean has stepped in and up as a maternal figure in my life and in Oʻahu, representing not just my biological mother, but also my island mother. The ocean is this caretaker/caregiver for a daughter who had to leave behind her CHamoru family.

Taijeron: I think the way you talk about the people in this book is very beautiful. My second to last question was about a pattern I noticed. Each of the sections, Origins, Taking Flight, Return, begin with poems about a mother. “Ocean Mapping | Apapa” begins Origins, then “Introspection” begins Taking Flight, and “Trongkon Nunu” begins your final section, Return. What does it mean to begin each of these sections with a body that brings about life?

Taitano Lowe: What’s funny is I never noticed, and that tends to happen with my poems, where they have a mind of their own. They like to congregate on their own too. It just felt right to open each section with those poems. I knew I wanted “Trongkon Nunu” to open the last section because it’s one of my favorite poems in the book. I feel very confident about that poem. I knew I wanted to start the last section very strong with “Introspection.” It felt right at the time to mark that section about leaving home for the first time with introspective reflection. It made sense to start with “Ocean Mapping” because of place. I thought about different things when I chose these poems, but I’m not surprised there’s a mother in each of them.

I’m happy you found those aspects. There tends to be relationships between poems I don’t notice right away. Another example is I didn’t realize how much I had woven in this metaphor and theme of weaving throughout the book. I really believe in Brandy Nālani McDougall’s notion of “ancestral intervention” in her book Finding Meaning: Kaona and Contemporary Hawaiian Literature (2016). Sometimes ancestors put things for me in these poems and I find them later.

Taijeron: Do you have anything else you absolutely want to tell people who are reading Ocean Mother?

Taitano Lowe: I really just hope this can be a space to feel safe and remind us, no matter where we are in our journeys in life: family, academics, career, whatever challenges, we always have our ocean. It’s always there. Maybe wherever we are the ocean looks a little different. Maybe it’s a little harder to get to, but it’s always there. And I hope as a community we can also just be that ocean for each other, “the fluidity of care,” to quote my interviewer, Lauren. That’s the most I can hope for.

Leave a comment