Review by Gabriella Contratto

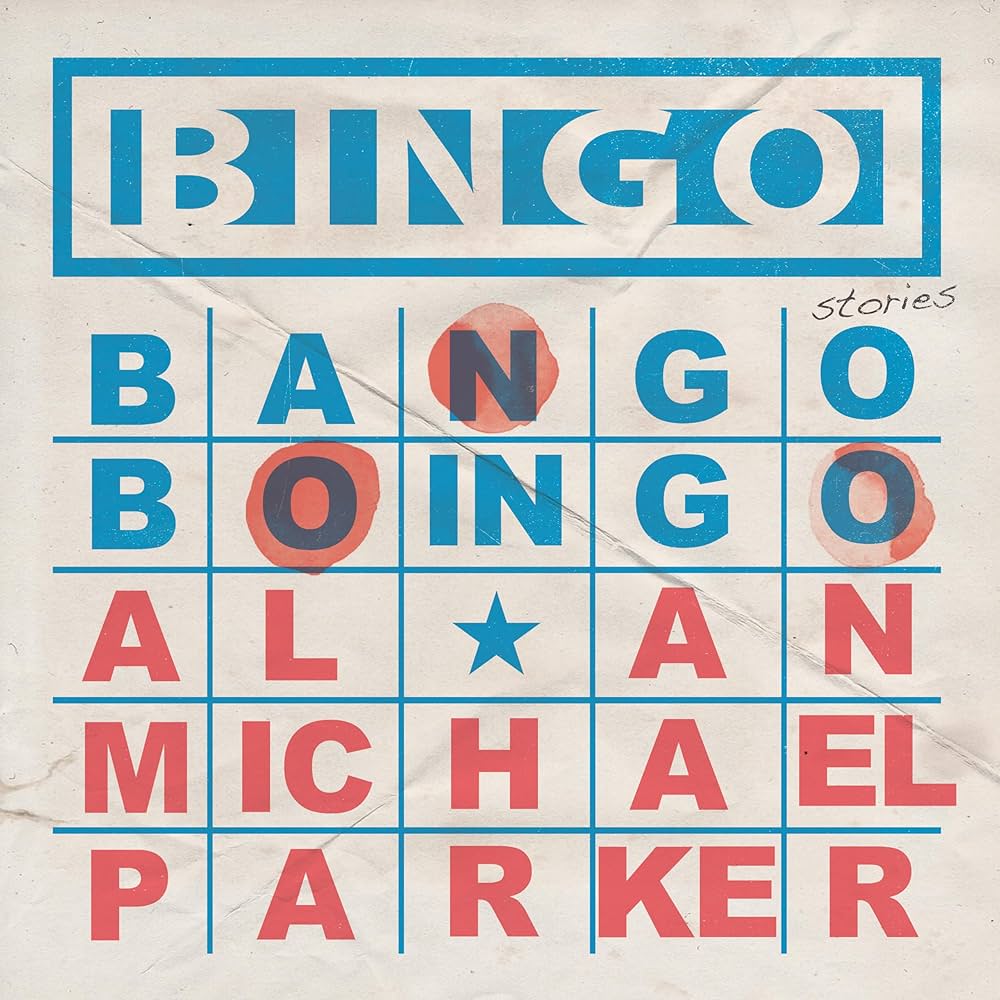

Occasionally I come across a book that upends my previously held expectations of how to form a narrative. Alan Michael Parker’s upcoming collection of flash fiction Bingo Bango Boingo (2025) is such a book. The book alternates between stand alone flash fiction, and stories presented as bingo cards. The flash is fantastic. Parker shows mastery over the form with pieces of varying length and style; his long career in poetry and flash fiction manifests itself in the strength of his writing and the imagery packed into the tiny boxes of a bingo card. By arranging those boxes together on a card, even a single word, “Yes”, becomes a lens that transforms how you view the other boxes in “Fetí’s Border Crossing Bingo”. With each flash story ranging from one to four pages, Bingo Bango Boingo is the perfect length for a reader who wants to pick up a quick read. It is an excellent addition to the bookshelf of those interested in a book that they can pick up and read a story or two at a time, or a creative writer searching for examples to model their own flash fiction off of.

Bingo Bango Boingo stands out from other collections of flash fiction due to the excellence of its genre-bending bingo cards. For most of the book the cards are completely filled out, although it is important to note that no one has played bingo on them yet. The reader must consider how the boxes could be combined to form the story, with countless possible combinations that they could create. Just like regular bingo there is one card in the center which is bolded and is the key to get five in a row. Presumably, if the reader follows the possible rows they will understand the story contained within them.

But how does the reader choose which rows? In bingo there are four possible combinations that let a person win: diagonally left to right, diagonally right to left, up and down, and straight across. Approach the cards like the real game and you realize that the boxes will not fill out neatly, in a left to right manner one at a time.

This causes the interesting effect of letting the reader’s mind create the story as their eye wanders the page. In most cards it is obvious that some boxes are clearly the subject’s thoughts, but when does the subject think that thought? In “First Day of School Bingo” does the student think “Freedom is the opposite of Time” before or after they are asked “‘Where did you go to school?” Since the box about freedom doesn’t contribute to winning the bingo, is the character even asked that? On a bingo card there will always be boxes that don’t fall into one of the winning combinations, but this doesn’t mean they are less a part of the narrative than the others, the reader must consider which boxes are “punched” and which are not. While the bingo cards make for quick reads–there are, after all, only twenty-five boxes a page–it’s the wondering about what happens that keeps a reader on the page for far longer than its short word count would necessitate. Sometimes on particularly heartbreaking bingo cards, I imagine that the worst boxes didn’t happen. Yet those boxes still exist, and the version of a narrative where “Mom dies” or “Dad dies” haunts my imagination.This does not mean the reader is entirely beholden to the cards filled with doom and gloom. The cards range in emotion from darker, to more contemplative, to downright hilarious– “A September Wedding, Not Hers” deserves special recognition just for the box “Overheard: ‘Honey I’m ovulating’”. Parker’s ability to convey snippets of scenes in the barest of lines is what causes this format to work so well.

Parker doesn’t just bask in his own brilliance with this form, halfway through the book he invites the reader to try it themselves. For example, Parker includes five cards with the title filled out, giving the reader the basic premise, as well as the center box and five to seven other boxes filled out. He leaves the rest of the cards blank, and filling them out–finishing the story–falls to the reader. This is a fun creative writing exercise that anyone can do, regardless of their experience, and by this point the reader will have seen enough examples that they can imagine the rest of the story easily enough. The thought provoking part of the exercise is determining what each box should contain; what should be included, or excluded in the limited number of boxes.

I filled out “Maya Sees a Moose” first, as I was drawn to the possibilities of flight or fight that the situation provided. Still, I found myself hand-wringing at times over what scene would get the coveted box that leads to bingo, and how they would tie together–or not. In my “Maya Sees a Moose,” Maya is alternatively despairing and wondering, freezing and in motion, thinking and blanking out. But that is my version of this card, and other readers could create a different story of what happens to Maya.

Parker has written Bingo Bango Boingo as a thoughtful, entertaining, and engaging collection of flash fiction and bingo cards, with something in it for every reader. As the book claims on its back cover, you’ll probably like it.

Gabriella Contratto is a second year MA student in the Creative Writing track. Originally from Los Angeles, she earned her BA at USC in Narrative Studies and minored in Cinematic Arts. She favors prose writing, and is particularly fond of speculative fiction, but her interests include Filipino culture/diasporic writing, LGBT+ communities, and Angeleno communities.

Leave a comment