by Alexa Cho

Leanne Dunic is a biracial and bisexual multidisciplinary artist. She is the fiction editor at Tahoma Literary Review, a mentor at Simon Fraser University’s The Writer’s Studio, and the leader of the band The Deep Cove. Her most recent project is a book of lyric prose and photographs entitled, Wet (Talonbooks 2024). Leanne lives on the unceded and occupied Traditional Territories of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh First Nations.

I was honored to have the opportunity to talk with Leanne Dunic during a tranquil autumn sunset at University of Hawaiʻi’s Mānoa campus. I spoke to her about the recent release of her multimedia book Wet, a story about a Chinese American model navigating her life in Singapore amongst a toxic atmosphere of persistent forest fires and exploitative working conditions. I learned more about Dunic’s travels across the world, the importance of non-human perspectives, and our connection to the lives around us. Hearing about Dunic’s receptive and flexible style of creation taught me the importance of turning attention away from the world’s comforting illusions and pursuing valuable stories yet untold.

This interview has been edited and abbreviated for publication.

Alexa Cho: With the astounding number of issues you weaved into dynamic forms throughout the narrative, I had to know more about the approach you took to writing Wet. Why did you choose to write a fictionalized narrative instead of something biographical like One and Half of You?

Leanne Dunic: I have lived in Singapore on various occasions and always took notes when I lived there, observing people and environments. When I was in Singapore for an artist residency in 2015, there was a drought and forest fires. This experience is what inspired the book. I wrote a framework for Wet during this residency and then spent the next few years polishing it up and trying to add a fictional narrative to make it more interesting than just what my observations offered me.

Over the years I worked on it, one of the most compelling parts was witnessing a whole population wearing masks since the air quality was dangerous. And as I was developing Wet, COVID happened, and then everybody started wearing masks internationally. At first, that was one of the post-apocalyptic elements of Wet, but now it’s normalized. Though, I realized there was more than just that to the book. It continued onto the rights of migrant workers, climate disaster, themes of sexuality and identity, and non-human perspectives.

Cho: From the fires during your residency to your experiences during COVID and all that came after, did anything else change from when you first conceived Wet to where it is now?

Dunic: Yeah, it did. When I first started, I called it Hysteria, thinking about hysterics and also the archaic definition of hysteria in women’s health. I was going to focus a little bit more on those definitions, but as the book evolved, I shed that. There are still some elements of it in there, but the focus shifted.

Cho: What inspired you to change the focus to where you are right now?

Dunic: I think personal interests and wanting the book to mean more to me and to touch on issues that are really important to me. I eventually realized that the idea of a frenzy, or the archaic definitions of ‘hysteria,’ were less a part of the manuscript. Instead, the book grew into one about the plight of migrant workers, desire, nonhuman lives, and the Pyrocene. While forest fires in my life incited this manuscript, they’re something that continues to be a part of my life and the lives of many, so it’s impossible for me to not write about them and their consequences.

Cho: It’s fascinating how all those experiences and voices come together in the text. To speak on that mix of voices, I wanted to touch on how Singapore is home to a mix of Chinese, Malay, Tamil, and other different ethnic groups. In that context, why did you craft your narrator as a Chinese American in Singapore?

Dunic: Well, in the original idea, the narrator was meant to be American because I wanted to write a little bit more about American gun violence. But as a Chinese American model, the narrator passes for a local. There’s a tension between passing and actually being an outsider that I found interesting.

Cho: Expanding on the idea of the narrator, how did you go about creating the voice in this piece?

Dunic: It’s inspired by my own experiences. For the voice, I imagined what it might feel like to be an Asian American woman. How would that be different from that of an Asian Canadian woman? As I worked on this manuscript, countless instances of gun violence occurred in the USA, especially against BIPOC folks. While this is certainly a problem in Canada, too, the threat of it in the USA seems to be amped. The sense of impending violence informed this narrator’s voice. So the voice came naturally. I don’t think I thought about the voice as much as I thought about other components of the book when writing it.

Cho: Can you tell me what components those might be?

Dunic: Sure. Form is something I spent a lot of time thinking about. Theme is also important, such as how to make this book narratively interesting while encompassing all the different components: the plight of the migrant workers, the pigeons or the lizards, the weather. And when I say migrant workers, there are so many different kinds of migrant workers that hold up Singapore—they account for a third of Singapore’s workforce. So making the narrator a type of migrant worker was really important to me. She comes from a perceived privilege as far as migrant work is concerned because she’s a model. But I wanted to show that modeling is also not exactly a luxurious form of work.

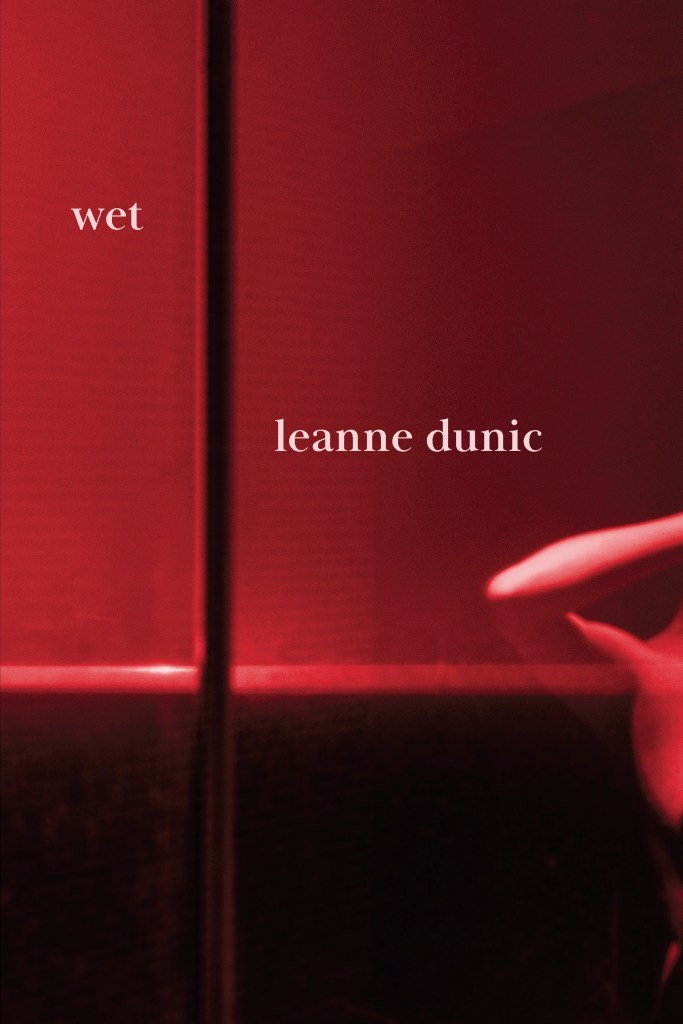

Cho: Speaking of the innovative components included in the book, one of the major things that caught my attention in Wet is the use of photos. I noticed that many of the photographs of people in Wet stray between two extremes, being either candid shots or close, intimate pictures like the one on the cover. The few exceptions are the human-like objects with the statues and dolls. What principles guided these decisions when including photos in Wet?

Dunic: Thank you for noticing them. I don’t believe in taking identifiable photos of people without their permission. So, if there is an actual human in a photo, it’s from a distance or it’s obscured enough that they are anonymous. I think it was important to show the variety of lives in Singapore. There were some people in there, but I also tried to show the nonhuman residents. For example, there’s a photo of a hand and there’s also an almost minuscule bug on the hand. Or there’s the mannequins that show up throughout to allude to the fashion industry, modeling, consumption, and capitalism. There’s symbolism behind all the photos, which was a big part of creating this manuscript—figuring out how to curate the sections of four photographs and what photographs to include.

Cho: It’s illuminating to learn your thought process on our responsibilities when portraying a population like Singapore’s, a group that goes beyond us as humans. I noticed that the main character herself is in this liminal state as a migrant worker, an identity fuels many conflicts in the book. I was curious about why migrant workers were what caught your attention for this narrative.

Dunic: Well, I tried to show this in the book, but it’s very clear that Singapore’s perceived prosperousness is at the cost of the welfare of migrant workers from Myanmar, Bangladesh, the Philippines, Malaysia, Indonesia, and China. These people hold up the country. These people are doing jobs that Singaporeans don’t want to do, and they are treated poorly. Migrant workers live in really, really poor conditions. Their health and safety is neglected. Construction workers are transported on lorries full of people, which is dangerous and dehumanizing. And so I wanted to draw attention to this because people often talk about Singapore as this idyllic place, a place that makes these amazing buildings that is a functional melting pot culturally, which is an illusion.

Still, it is a complicated place, and I acknowledge that I’m an outsider who does not live there. Observerving these complications helps us think about the complications in our own countries. I’m from Canada. We are not exempt from treating people and other earthkin poorly. The United States certainly isn’t exempt from that too. I guess I’m just trying to draw more awareness to these issues.

Cho: Yeah, many of these criticisms against Singapore are also something that can be applied to Hawaiʻi and how Native Hawaiians can’t afford land on the islands anymore. These sentiments are relevant to many issues going on in the world right now.

I actually did think of Singapore as, like you said, a highly successful, distinctly affluent country that stands out in quality of living compared to other Asian countries. However, the inhabitants of Wet struggle with the high cost of living, the low air quality, and other challenges you mentioned like the migrant workers’ plight. How do these elements—the public perception, your own experiences, and research—come together?

Dunic: I would say Singapore has a public image. Some people, even Singaporeans, believe the public image. But it’s easy to ignore truths. If you’re looking for a take on the country and its challenges from someone who was born and raised in Singapore, I strongly recommend Dinner on Monster Island by Tania De Rozario. She offers a feminist, queer perspective on what it was like for her to grow up in the constraints that Singapore offers. Her book is a really great companion to my book. She tackles issues like modeling, fat shaming, and she even talks about migrant workers. We have a lot of parallel topics in our work, except she offers the perspective of someone who was born and raised there.

Cho: Sounds interesting! I’ll be sure to check her work out. To move into another aspect of the book, I noticed various animals appear in Wet and fill various roles. The narrator even likens herself to a rock dove early in the story. How would you describe the role the animals play in the narrative and how they compare to the role that humans play in the narrative?

Dunic: I was trying to bring attention and presence to our more-than-human citizens. I’m not as interested in human-centric work. This was my way of addressing that, you know––let’s stop just focusing on ourselves. There’s so much more to think about.

Cho: What do you think we can learn from nature?

Dunic: Oh, I mean that’s endless. We could just sit here at this table and find something that we could learn from if we spent the time and the intention.

Cho: For sure. As much as industrialization has spread across the world, nature still surrounds us and, in a way, is more meaningful than ever. One recurring natural image that I noticed in Wet was the idea of the pigeons and the birds. Do they serve a particular role in the book or a reason they were featured so heavily?

Dunic: They’re very present in pretty much every major city in the world, so they are often thought of as a pest. And to me, they’re these wondrous, resilient creatures that we should respect and care for. Once, I was hiking Diamond Head. At that time, I saw a gentleman feeding pigeons out of his van, and that scene actually made it into the book because I wasn’t sure if he was feeding them or poisoning them. And I thought that was a really interesting moment.

Cho: It’s amazing how your experiences have come together like this and how universal these birds have become around the world! From what I mentioned earlier about the narrator as a migrant worker liking herself to a rock dove, do you think there is a connection in the book between the migrant workers and the pigeons or animals?

Dunic: There’s a connection in everything if you want to find it. One of the photos in the book is a picture of pigeons, and you can’t quite tell, but they look a little off. I believe they look the way they do because they fell in oil from a nearby hawker stall1. They’re a proxy to understanding our impact because they’re so present in daily life. If we look at them, we can see how we’re taking care of them, or neglecting them, or how they are affected. You’ll see pigeons without legs, or missing an eye, or with avian flu, or whatever the case may be. If we look at these images, we have questions to ask ourselves about what we’re doing and how it’s affecting others. What are the practices in place to protect others from harm that happens because of our carelessness? I used to work at a wildlife rescue, and the number of times we would get skunks with their heads through plastic rings, or birds stuck in garbage, or animals that come in convulsing because they accidentally ate a rat that was poisoned… When you look to the animals, you see how many ways we’re failing as humans.

Cho: Is that one of the important themes you want people to take away from Wet?

Dunic: Maybe to just have some more compassion for all beings. One of the migrant workers in the book is a maid who lives behind a bookshelf. Then there are construction workers. There are masseuses of different ages and cultures. So many different kinds of workers hold our societies together. Any metropolis is held together by migrant workers. It’s very easy to dismiss that. They deserve fair treatment.

There’s an organization I mentioned in the back of the book called HOME, and they have been around for over a decade at least. They fight for the rights of migrant workers. And so I encourage anyone who’s interested in learning more about what the situation is like to check out their website.

Cho: Going off this idea of nature and having connections to all things, I noticed that one of the key aspects of Wet is, of course, water and wetness. It runs through the people, runs through the animals, and runs through the elements of love and sex. Why did you decide on this element of water and wetness to be your central focus in the book?

Dunic: It emerged organically. But the reality is the situation at the time was very dry. You’re just longing for the relentless heat and dryness to end, and I think that speaks to a lot of other things that we long for. So it’s a metaphor. It’s literal. As you say, it has different applications to different themes in the book. Water is connecting. We all need it.

Cho: How do you decide how to mediate and organize these larger questions or ideas in your book?

Dunic: Well, I don’t want to beat people over the head. I don’t want to shame readers into feeling like they’re bad people or there’s nothing that they can do. I want to present some observations and let the reader walk away with what they walk away with. I am trying to be somewhat subtle and gentle with my presentation because I hope that the lighter approach will not discourage people from finding ways to make differences in their lives.

Cho: To conclude our interview, I wanted to bring attention to your upcoming work Salt Rich and get a little sneak peek on it for curious readers. In particular, how did the elements of Wet carry over or change in between these two books?

Dunic: Coming from a family and ancestors that lived on an island, I cannot escape water. Salt Rich is a chapbook focused on the lives of my grandparents who fled the former Yugoslavia, eventually coming to Canada. They were fisher people, hunters, and farmers, so salt water was a really big part of my upbringing and our way of living as a family. The title and the theme of the book still have components of water. I cannot escape water and wetness. My band is called The Deep Cove. The band who did the soundtrack for One and a Half of You was half of The Deep Cove, and so we called ourselves tidepools. The water is always there.

1A food stall in a “hawker center,” typically referring to an open-air food court in Southeast Asia

Alexa Cho is a Native Hawaiian senior undergraduate who is currently studying English and Japanese. She enjoys writing prose fiction in a mixture of genres and on an assortment of themes, taking particular interest in the imaginative power of speculative fiction and dark fairy tales. Through her time with Mānoa Journal, she hopes to interact with stories from all corners of the Pacific

Leave a comment