by Andrew Hoe

A friend from Big Island recently told me how Rick Riordan’s Kane Chronicles were foundational to him as a child, and I, also being a fan of Riordan, brought up the Rick Riordan Presents books. My friend lamented that, while there were so many cultures represented in that wonderful series, there were currently no books about Pacific or island culture. He light-heartedly described the lack as “continent bias.” Were it not so late into the evening, our conversation would most likely have turned to YALO (Young Adult Literatures of Oceania), an ever-expanding literary movement that serves the children of the vast and mighty Pacific.

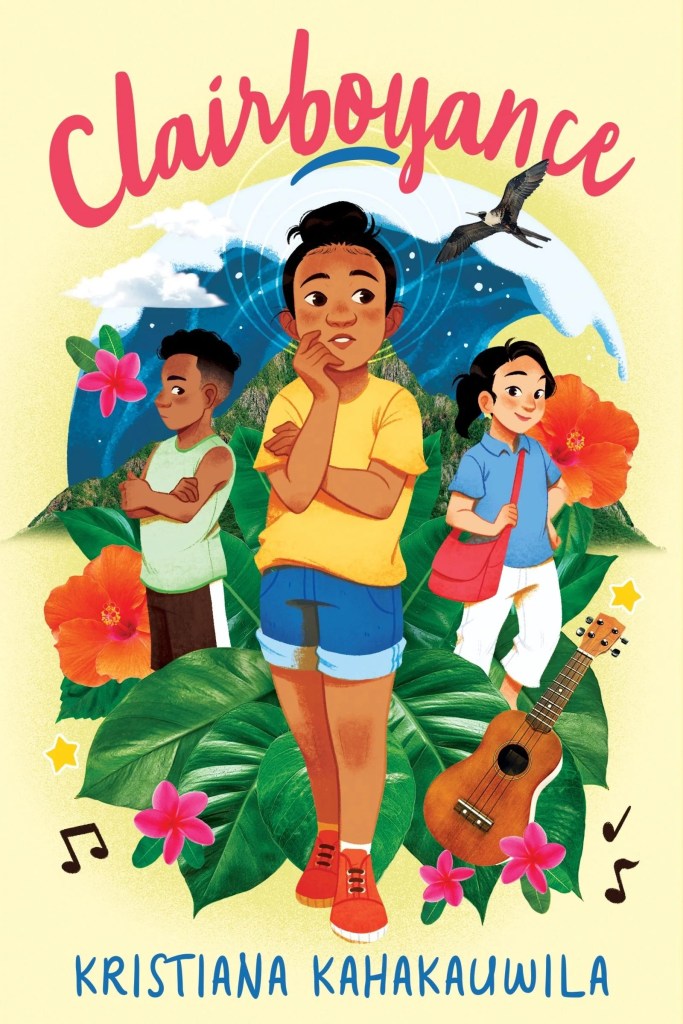

Kristiana Kahakauwila’s Clairboyance would be a worthy addition to the shelves of YALO. As a Maui-born author, Kahakauwila weaves a funny, heartfelt, and sincere tale of twelve-year-old Clara, who unwittingly makes a wish on her family’s ‘umeke and gains the ability to hear the thoughts of the boys around her. The messes Clara finds herself in through this hilarious talent are just as much about finding herself as deepening her understanding of being Kānaka Maoli.

Love of Oʻahu is ever-present in Clara’s story, and readers will find themselves falling in love with her beloved home too—even as she starts her story desperately wanting to move to Arizona. As Clara plots to speed up her departure date, she is reminded of Hawaiʻi as an abundant source of life (aloha ‘āina) and of her relationships with her family community (pilina). Clara’s tūtū raises kalo on a verdant hill plantation, and Clara discovers that others in her family and on the island have special abilities. One uncle, possessing the ability to hear the thoughts of fish, accidentally upsets the delicate balance of life through overfishing and must repair the damage. In this way, off-island readers will find themselves gently educated about island ways of respecting the flora and fauna as neighbors and relatives to Native Hawaiians, not produce to be exploited or garden vegetation to be pruned. The novel finds ways to playfully hint at this indigenous epistemology regarding the deep connection between humans and more-than-human persons. For instance, Clara’s nickname is Shrub, the story of Hāloa and kalo is referenced, and some choice personification is used—like a depiction of leaves that “bob up and down in relief when we leave, as if the taro has been waiting to relax” (249). A particular ‘iwa bird takes an especially keen interest in Clara!

Young readers feeling socially awkward may find themselves drawn in as Clara finds herself tempted to use her newfound ability to get that crucial edge in navigating middle school life—to hilarious consequences. Dubbed a mouse by the popular kids, Clara uses her mind-reading to try to figure out why her former best friend now dislikes her, causing two male friends to fight in the process. Clara’s scramble to fix things causes more problems, but she learns that she isn’t the only person in middle school who feels disconnected. Kahakauwila’s handling of middle school hijinks is sensitively rendered—along with how boys at that age think—and Clara finds herself on group life science projects with new friends that involve visiting a heiau and harvesting kalo. In particular, there’s a mapping project that introduces her to the concept of 3D versus 2D charting.

Here, Kahakauwila works in a surprising amount of political argument regarding the real-life struggle of Native Hawaiians against zealous developers who misrepresent terrain to justify more projects. “I imagine,” Clara states while trekking about the island with her classmates, “sandalwood and koa trees blanketing the slope. Yellow ‘amakihi and ‘alauahio trilling among the branches. And the water moving freely. No private property to interfere with its course to the sea” (161). Heavy and contentious topics like the 2009 protest against industrialization of agricultural space in Wai’anae (called Purple Spot) do not appear, but Clara’s understanding of how the ‘āina appears on maps becomes key to understanding her father, who is a construction manager, needing to move to Arizona—and take Clara with him. Readers empathizing with Hawaiʻi’s ongoing plight of development catastrophe, like the proposed TMT project on Mauna Kea and Red Hill spillage disaster, will note that when Clara learns to map the island’s landmarks and abundant qualities, she makes the subtle argument that the 2D maps contractors use to claim Hawaiʻi as a barren wasteland in need of development are false.

This message is gently repeated by the novel’s heart—its characters. Clara’s principal, Kumu Apo, tells her,

Oceania is the biggest region in the world. We’re part of that. We’ve got big stories… Maybe, all alone, your story is on the small side. Most stories, taken by themselves, can feel that way. Like how an island that stands alone in a huge sea can look small. But if you stop looking at that one island and instead see how it’s part of a whole archipelago, how the Pacific is filled with islands, then you might start to notice how big your story actually is. How much space and time and how many connections it covers. (125)

The wisdom of Clara’s elders is a nod to the Native Hawaiian respect towards kūpuna. Clara gains necessary insight regarding her clairboyance from her tūtū and from a māhū teacher, and the novel’s messages towards diversity and inclusion are well done. Clara’s middle school peers come from various heritages and include mixed-race children and account for diasporic Hawaiians who return to the island.

In essence, Clara’s story is a novel about re-homing—learning more about her beloved island and why it’s so beloved—but it’s also a novel about finding family. Friendships Clara didn’t think possible emerge and those that Clara thought irreparably broken become stronger than ever. It is a novel written by someone whose love of the islands comes through in every chapter and every sentence. I can’t speak for how my Big Island friend would enjoy Clairboyance, but I will definitely bring it up in our next conversation.

Andrew K Hoe is a children’s and speculative fiction author whose work appears in Beneath Ceaseless Skies, Diabolical Plots, Highlights for Children, and other venues. He is excited to be included in this latest issue of Mānoa Journal. Find out more at andrewkhoe.wordpress.com.

Leave a comment