Emily Jungmin Yoon is a poet, translator, editor, and scholar. She is the author of the full-length poetry collection A Cruelty Special to Our Species (Ecco | HarperCollins 2018), winner of the 2019 Devil’s Kitchen Reading Award, and finalist for the 2020 Kate Tufts Discovery Award. The book was released in Korean as 우리 종족의 특별한 잔인함 (trans. Han Yujoo, Yolimwon 2020). She is also the author of Ordinary Misfortunes, the 2017 winner of the Sunken Garden Chapbook Prize by Tupelo Press (selected by Maggie Smith), and the translator and editor of Against Healing: Nine Korean Poets (Tilted Axis 2019), a chapbook anthology of poems by Korean women writers. Yoon is currently working on a critical manuscript, Enclosed Reading: A Feminist Method for Contemporary Korean and Korean American Women’s Poetry, 1987-2019. She is an Assistant Professor of Korean literature at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa.

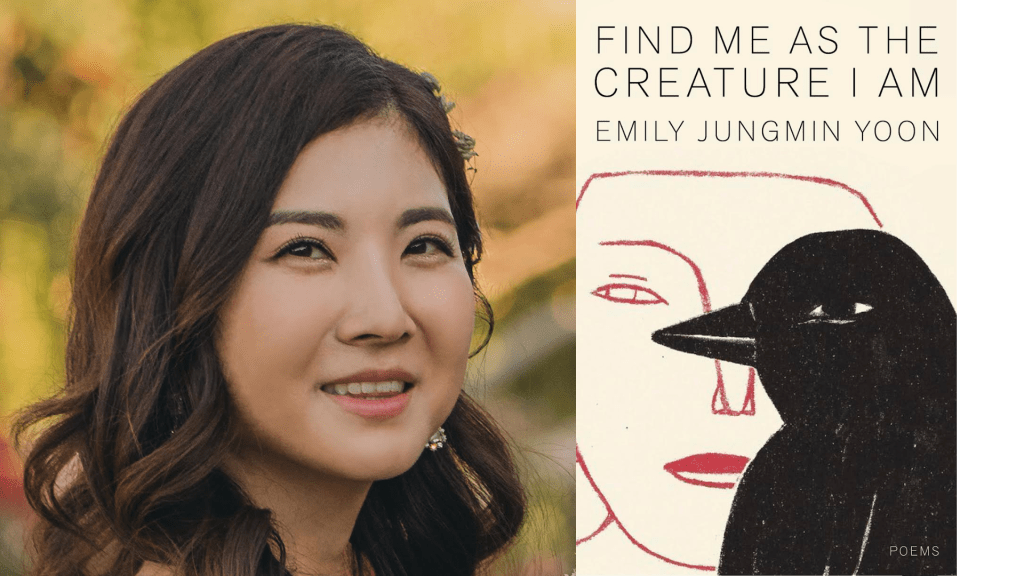

Yoon’s second full-length poetry collection, Find Me as the Creature I Am, is out now from Alfred A. Knopf in 2024.

This conversation was held in front of an audience at the 2024 Hawai‘i Book & Music Festival on September 15th in Honolulu on the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Campus, and it has been abbreviated for length.

Amanda Galvan Huynh (Galvan Huynh): In your new collection, you’re carrying many concerns facing humans right now: climate change, environmental racism, and survival to name a few. Enough to create some anxiety when I, like most others, sit with those realities for any length of time. However, to me at least—so correct me if I’m wrong—you are not resisting these enormous events that are out of your control. Through your writing it feels as if you are surrendering or transforming intense realities into beauty. I’m specifically thinking about the poem “Affection” from the lines “red slopes / and orbs mapping deaths from the virus, from fire, from firearms” to “and yet / red roses.” How do you ground yourself before or after you start a poem like this or just a poem with difficult content? And then how do you return to revise a poem like this one? In what ways do you find strength to move forward?

Emily Jungmin Yoon (Yoon): Thank you so much for that multifaceted, multilayered question. I don’t know, to be honest. But I did think a lot about climate dread. We’re all feeling it. But what does it mean to thread it into poetry? And I was thinking: Why did I even choose poetry as my medium? Or why did it choose me?

For me, poetry is about preserving a moment. I mean, there is epic poetry and lengthy poetry as well, but I think it’s a lot about capturing the moment when you realize that you’re in love with this person, or when you realize maybe you don’t like the way your life is going right now. You know that kind of moment. I wanted to make poetry that helps me dwell in those moments a little longer, but also think about what it means to transform it into beauty, and the power of beauty as a whole. Beauty is not necessarily something that’s pleasant or symmetrical, but a force that makes us continue looking at something. That makes us unable to look away.

There are really kind of fearful sentiments like “Oh gosh, the world is on fire” and “Oh gosh, what’s going to happen fifty years from now?” I wanted to try and crystallize that moment, be in it, and create beauty in order to make me stay in it longer. I know it sounds a bit jumbled, but I’m figuring that out myself as well.

I return to the quote by Toni Morrison—perhaps you’ve heard of it—where she says, “I think of beauty as an absolute necessity. I don’t think it’s a privilege or an indulgence, it’s not even a quest. I think it’s almost like knowledge, which is to say, it’s what we were born for.” And she’s saying this in the context of an interviewer saying to her, “Your novels are of great beauty.” But as some of you know, her novels deal with the dark history of America and slavery. What does it mean to create beauty from that? Her answer really resonated with me as I examine poetry as a lens through which I think about these issues.

The second part of your question was how do I kind of come back when I want to revise. I think a lot of us will have the same approach, if you’re writers or if you’re creating anything: taking the time to step away from the work and coming back. When I write, I write in spurts of energy, and I revise as I write too. If I’m writing for a long time, then I also tend to get lost in it. I find myself thinking, “I’m not sure if it even makes sense or sounds good anymore.” So I really need to consciously tear myself off the poem, do something to care for my body, and then come back to it with fresh eyes.

Galvan Huynh: With the mention of Toni Morrison’s quote, it brings to mind what happens when we are face-to-face with darkness, when we’re writing about dark and difficult things, and how we take care of each other. It makes me think about how we create moments of mercy and breath. There were these breaths that you had built in, and throughout this collection, you give readers moments of mercy. For myself I was drawn to this line: “Every day someone leans the shovel / and knife, real and not, against a gentler thing” in “The Blades.” Can you talk about your thinking behind these moments and how you craft mercy into specific lines, into space, or even into breath?

Yoon: Thank you. I really appreciate that question, Amanda, about mercy for the readers because I really want my poems to not be hurtful. I don’t want it to cause pain or agony.

Well, you know, that’s kind of hypocritical because a lot of these poems are about terrible things, terror, and I want you to be there with me. But I do want those moments of mercy and rest. That was a word I wasn’t thinking about that you illuminated in me. For this second book, I thought a lot about tenderness because my first book’s driving and emotional engine behind it was sorrow and anger. Those poems revolved around the history of the former “comfort women,” the sex slaves of the Japanese Empire, this turbulent South Korean history, and my role as a witness in a postmemory generation, so it made sense for anger to be the ingredient for these poems.

For the second book, I really wanted to think about what it means to care for myself and others even while feeling those emotions. I want to paraphrase something Ocean Vuong said a few years ago when Vuong’s novel On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous came out. He said, “What comes after these emotions? These hard emotions, like when you become really angry and scream. What do you do afterward? Maybe you light a candle, or take a bath. You care for your body.” I forget in which context he said it, but we were in something similar to this [interview] where I was in conversation with him. But it resonated with me, and those emotions were things I wanted to craft my poetry around for this collection, and to see what happens. So I am glad those pockets of mercy emerged.

Your question centered more on how I did it; though, I don’t know really. Maybe the meditation on tenderness helped me insert those moments into the poems without a concrete design.

Galvan Huynh: It’s okay if you don’t answer my question specifically. Whatever comes to mind or brings you to life is perfect. This next question is my favorite one as I’ve been excited to ask it. Can we talk about forgiveness and the body and being a woman? And this line: “I loved to forgive because it meant I was a goddess”? If not my favorite line from this collection, it’s up at the top. Your poem “Decency” made me ask: Who does forgiveness belong to? Why does it have to come from women or from men? Does it always come from women? From the bodies of women (thinking to “Body Of” and ahead to “I leave Asia and become Asian” too)? Where is the body and forgiveness intersecting in your work—if at all?

Yoon: Not to get into all the weeds and details, but I had to learn forgiveness at a very young age just because of some circumstances in my life. It’s still something that’s hard for me to write about. Not to mention to talk about. And I think that’s where that poem came from. It also arises from other contexts, too, as a woman who had to be the manager of emotions when things were not my fault. But of course other people were feeling their things. And even if I was upset too, I had to take care of their feelings. I feel like I’ve just been in that position a lot in my life.

I think it’s a very common experience for women, and I can’t go into too much detail about “Decency” right now, but I was able to squeeze out this poem that surrounds this truth and reality.

When it came to the body, I had thought a lot about it too as I was writing this book. Especially because the middle section of my book is actually a poem that I wrote as an essay—it was published as an essay—and it is about the Atlanta Spa Shooting and the women’s bodies becoming repositories of male desire and them being punished for it.

I was also thinking a lot about the functions of my body in male spaces or with male acquaintances. I have one person who would always tell me to have babies, and it infuriated me so much, but I wasn’t able to be in conversation with him about how messed up that is. So all these unresolved frustrations manifested as some of these poems.

Galvan Huynh: In “I leave Asia and become Asian” you weave together quite a few social issues that I had a bit of difficulty choosing where to start this next question because there are so many layers to move through—which is a wonderful thing. The center focuses on “becoming” and becoming othered/Asian when in proximity to the American/Anglo-centric gaze.

Naturally, I want to ask about how living in different countries impacts your thinking and use of language, but then I pause and think about how culture, more specifically gun culture and violence, can also impact how we think, relate, and grieve certain events. I note this because of the line “Forty years later, gun violence is unfathomable in South Korea” and how it contrasts with the moments where you give tribute to the six Asian women who died while working in the Atlanta Spa Shootings on March 16, 2021. Can you talk about your experience moving (and living) from South Korea to Canada to America to Hawai‘i? How did or do those experiences transform your thinking around language, writing, and what it means to be part of a grieving collective?

Yoon: That’s something else I’m thinking a lot about these days, especially now that I live in Hawai‘i. For those of you who don’t know, I moved to Canada when I was almost eleven years old, and that was the first time I heard the word “Asian,” or the first time I remember being called that because in Korea, we don’t say we’re Asian; we’re Korean. I wrote this into the poem that I felt simultaneously more and less than Korean. That was the first time I felt like, okay, I’m the other, I’m not part of the mainstream. I was in Victoria, British Columbia, where I can’t say I had a particularly tumultuous experience. Generally, it’s a nice place to be, but it was still maybe 70% white; being Korean is trendy now, but back then, people would be so disappointed that I’m not Japanese or Chinese. They would always ask me, “Can you teach me how to say this in Japanese (or in Chinese)?”

I’d always have to say, “I don’t know, I’m not from Japan.” Being in that zone of alienation was very strange. In Canada, I felt like there’s this culture of pretending like racism doesn’t really exist because they’re too nice to be racist, and then in the U.S. it’s very much part of the conversation. Yet, the kinds of racially motivated crimes and events that happen in the U.S. are on a different scale than what I would witness in Canada. I came into a kind of Asian American awakening in the U.S. when I learned about the Asian American movement and the political coalition aspect of it. “Asian American” is not simply a racial category; it came out of a very conscious allegiance against the mainstream culture of whiteness.

Then I moved to Hawai‘i, and it’s a completely different conversation as well right now. I have never lived somewhere outside of Korea where so many people look like me. But then I think about the colonial condition that made this population that way, and who’s being displaced. I’m trying to make sense of my identity as a settler colonialist, which I admit I didn’t think about often when I was on the continent, because the way that I thought about race and ethnicity was in the dichotomous framework of whiteness versus everybody else. The relationship between Asians and indigeneity isn’t something that I had thought about as deeply; it’s a new learning experience for me. This identity and relationship are things I am very fearful of writing about or articulating into poetry because I still feel like I’m learning, but I think my next experiment for my next collection or whatever manuscript of writing will emerge from these ideas.

I think I’m going to try naming these fears and then look at other examples of how Asian immigrants have viewed Hawai‘i, the people, and the flora and fauna here, and their varying attitudes. And from there, I want to kind of identify myself within that while also creating a critical distance so that I may become a better guest of this land. It’s a really different positionality here than anything I have experienced before, and it sounds complicated and disorganized because it is; this is where I’m at right now with this.

Galvan Huynh: Since you mentioned your current thinkings around a potential next book, I want to turn our attention to the next “work in progress.” We’ve had a conversation about the “What are you working on now?” question and how much it can be embedded in the work we do as writers (even at the very moment we complete something), so I want to move away from the “What are you working on?” question, and instead I want to ask, what does your rest look like? What nourishes your body right now?

Yoon: I’ve been doing a lot of yoga. When I go to practice yoga, at home or at the studio, I feel like the teachings or the way they conduct sessions feel very similar to poetry workshops.

No‘u Revilla talked about failure yesterday, at a wonderful reading of three Hawaiian poets, and that reminded me of yoga because when I’m practicing yoga, the instructor reminds you, “Okay, if you can’t do this pose, there’s a way to modify it and continue.” You’re not failing: there are other ways to do it; you’re still using this muscle; you’re still getting better and going towards something that you need to be. So yoga does nourish me a lot. It helps to really own that time, and it’s similar to poetry because it’s slow. It can be fast, but most of the time it is a slow practice, holding poses and attuning to your body.

Another thing I’ve been trying is to have a book that I’m reading every day, even if it’s one paragraph. It’s helpful to have a catalog of books that I’m just reading for pleasure, because as teachers and students, we have readings assigned to us. Sometimes I forget how joyful it is to read and not feel like I need to analyze it or look at points to teach. So I take that moment for myself at the end of the day, and it’s been really helpful for me and for my soul.

Galvan Huynh: You’re right. It’s so difficult when we’re in academia to read for pleasure that it can feel like a luxurious sin when we do carve out the time for it. Thank you so much for your time today. I did want to ask a final question: Is there anything else you want to share with us?

Yoon: If I may, I’ll share some unsolicited advice; it’s something I said to my poetry workshop students this semester. Use kindness as a method for writing and moving forward with a poetry “career.” Practice kindness not as an easy, empty encouragement, but as a rigorous close reading for yourself and for each other—holding oneself and one another to a high standard, with wonder, generosity, and curiosity. Show up for one another on and off the page: share work, feedback, opportunities; literally show up for events. We are all we have.

Amanda Galvan Huynh (she/her) is a Xicana writer and educator from Texas. She is the author Where My Umbilical is Buried (Sundress Publications 2023), a chapbook Songs of Brujería (Big Lucks 2019), and Co-Editor of Of Color: Poets’ Ways of Making: An Anthology of Essays on Transformative Poetics (The Operating System 2019). She serves as the Managing Editor of Mānoa: A Pacific Journal of International Writing.

Leave a comment